Reminiscences of Helensburgh, Illawarra Historical Society Bulletin, February 1970

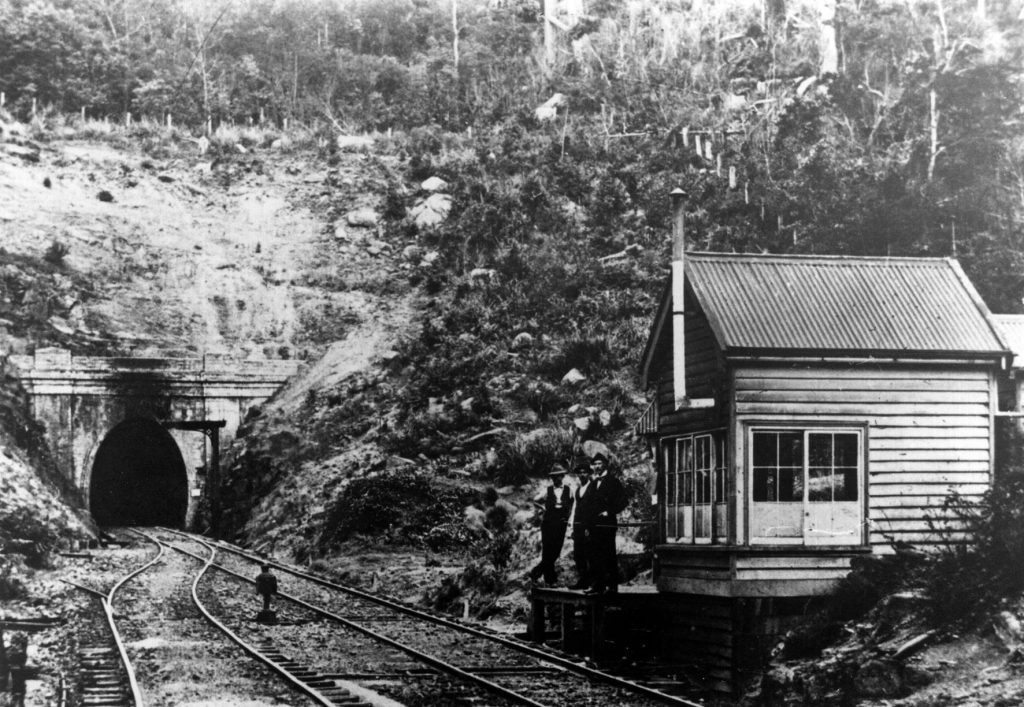

In my very young days, I lived at Borenore, 14 miles from Orange on the main railway line to Parkes and Forbes. In 1909 my father, a stationmaster, was transferred to Helensburgh – or to be more correct Metropolitan Junction – at the junction of then main line and the line leading to the colliery of the same name. Helensburgh Station – the old one – was between two tunnels, one at each end of the platform, and was purely a passenger platform. There was no railway business there of any consequence other than passenger. Metropolitan Junction was another story. The mine was the biggest on the coast in those days and the main – practically the only – support of the local people. The coal went mainly to the Everleigh Loco sheds and was one of the principal sources of supply for the New South Wales railways, all of them steam. Diesel engines were in the distant future. There was plenty of work, recording outgoing coal and incoming trucks for the man in charge of the Junction station, a signal box with a small wooden platform for visitors. Trains, because of the lack of facilities in the mine yards, were small. At Waterfall there were marshalling yards, where destinations were sorted out, and much bigger loads pulled by more powerful engines made the trip to Sydney.

It was a long climb from the mine to where I lived. There were many thousands – well, hundreds – of steps to negotiate before you got to the top of the hill and that was not Helensburgh town. These steps were cut out of the hillside and old railway sleepers used to prevent the earth breaking away. All traces have disappeared nowadays, so far as I could see.

The road down to the mine was rough – no sealed highways then, nor buses for the men, they had to use the steps coming and going. We lived about half way between the passenger station and the town. Across from us was Struggletown, a series of mostly dilapidated cottages straggling down the hillside.

We had about half an acre of ground at the back of the house, on which we ran our pony. By the way, this pony was a character in his own right. There were three of us children and when he was feeding at his trough we often climbed onto his back, all of us together, in the vain hope that he would take us for a ride around the paddock. Nothing of the sort. Without a tremor, he would march – that is the correct word – over to the clothesline – NOT a rotary one, they were unheard of in those days – and slowly and gently would scrape us off. No kicking, no fuss, but we ended up at his heels on the ground and he went back to his dinner.

Whether our family were the first or not, my father arrived home from Sydney one night with three pounds of grass seed of a type new to Helensburgh at any rate – paspalum. It was planted in the back paddock. It thrived and spread – all over the town. He said it was a revolutionary grass and so it was. I have been to Helensburgh recently but can find no traces of any monument erected in Dad’s honour. Remember, there were no motor mowers in those days or for many years to come and lawn mowing, or more particularly paspalum mowing was quite a task. Kikuyu came many years later and eventually pushed paspalum back to where it belongs – on the dairy farms.

Helensburgh was a small town then: a Post Office – the Railway Station was considered too far away to be considered a municipal ornament – a School of Arts and a police station. There were two schools, a Public and a Convent. The school books were much the same in both. I remember one boy who didn’t go to my school telling me that his history book when it came to Elizabeth I’s reign had “the good Queen Bess” altered clearly in ink to “the bad Queen Bess”. I was scandalised at the time, but I’m not sure now that his teacher was altogether wrong. You get a different conception of history when you grow older and continue to read – which not too many do, by the way.

I remember we had a school concert in the hall attached to the School of Arts. I was taking a leading part and relatives came many miles, some even from Sydney, to see me perform. I was a postman, dressed for the part: long trousers, cap and all the trimming (as we didn’t say in those days). I walked onto the stage, handed a letter to the heroine and walked off, not saying a word, applauded to the skies (I think now as I look back, mainly by family and relatives). I have never played a more satisfactory role since.

Helensburgh has improved tremendously over the last sixty years, and where we depended on kerosine lights in the house and on the streets, they have all that goes with a modern town – why, they’ve almost got a swimming pool.

I noticed lately that some of the new arrivals are endeavouring to convert us to pronouncing the name as HELENSBOROUGH. Helensburg is good enough for me.

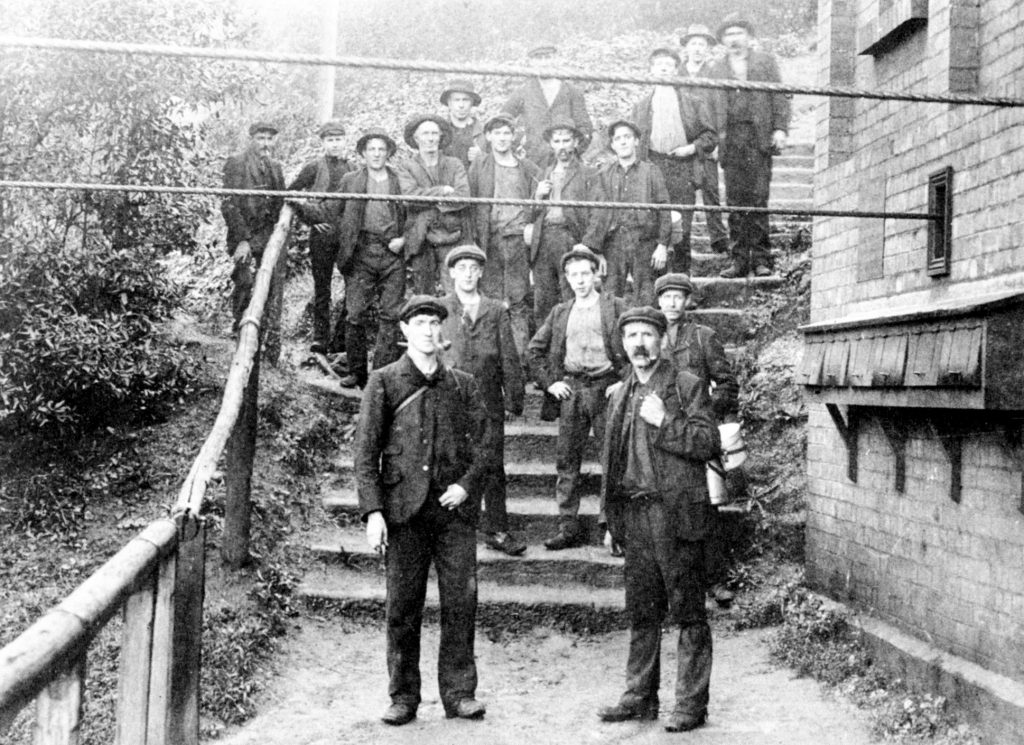

There were few or no amenities at the mines in those days. A miner walked to and from work (there were no conveyances then) and arrived home covered with coal dust and in his work clothes, bowyangs and all. Bowyangs were common – a piece of string tied just below the knee to keep the trousers clear of the ground to prevent any possibility of tripping over when working underground. They were not confined to miners, many other manual workers, labourers, railway fettlers, etc. used them. Bathrooms and present-day facilities at the mine head were in the distant future sixty years ago. You had a tub in front of the kitchen fire when you got home. There was no mechanisation. Coal was picked from the face, loaded into skips by shovel and hauled to the cage by pit ponies. These latter lived underground only coming to the surface in the event of strikes (which were not unknown in the early part of the century). A miner in those days was a miner in the dictionary sense of the word, not a machine operator as he is now.

I recently visited Helensburgh for the first time since 1910. The old Helensburgh Station has completely disappeared except for a few sandstone blocks in the creek at the back of where the railway buildings stood. The tunnels, or at least one of them, are occupied by mushroom growers – the fate of the old Otford tunnel too. A comedown from earlier times.

Whether these reminiscences of a nine year old have any value I’m not sure, but it is surprising to me how much one can remember of those times. If I have succeeded in stirring up some interest in the far away part of our city, I am well satisfied. Perhaps someone will write a full history – in the not-to-distant future, or I may not be around to see if it agrees with my picture of the town in the balmy days before the First World War.